The Good Field

Part 1: A Most Goodly Field

Due to recent developments regarding this particular subject, I thought it might be rewarding to revisit an article written in 2022 about a local plot of land that has become important to my partner and I. The first half is presented below, and provides a little bit of context for the discovery of, and first thoughts on engaging with this Field in England. The second part will follow shortly and will explore how this relationship has changed during the past two years.

One of the few mercies that Covid bestowed upon us was what would become known as the Good Field. Although my partner and I were familiar with the shoulder of woodland that sits west of the Dee Valley and spills southwards from Chester to Eccleston, the Good Field became the focal point of fire-lit, evening meetings with friends. In previous years, access to the field had been limited due to a multitude of grazing horses which don’t make for ideal picnic guests. However, with their sudden disappearance, exploration of this parcel of land become possible and, for the duration of the plague, the Good Field was a source of dependable, peaceful escape.

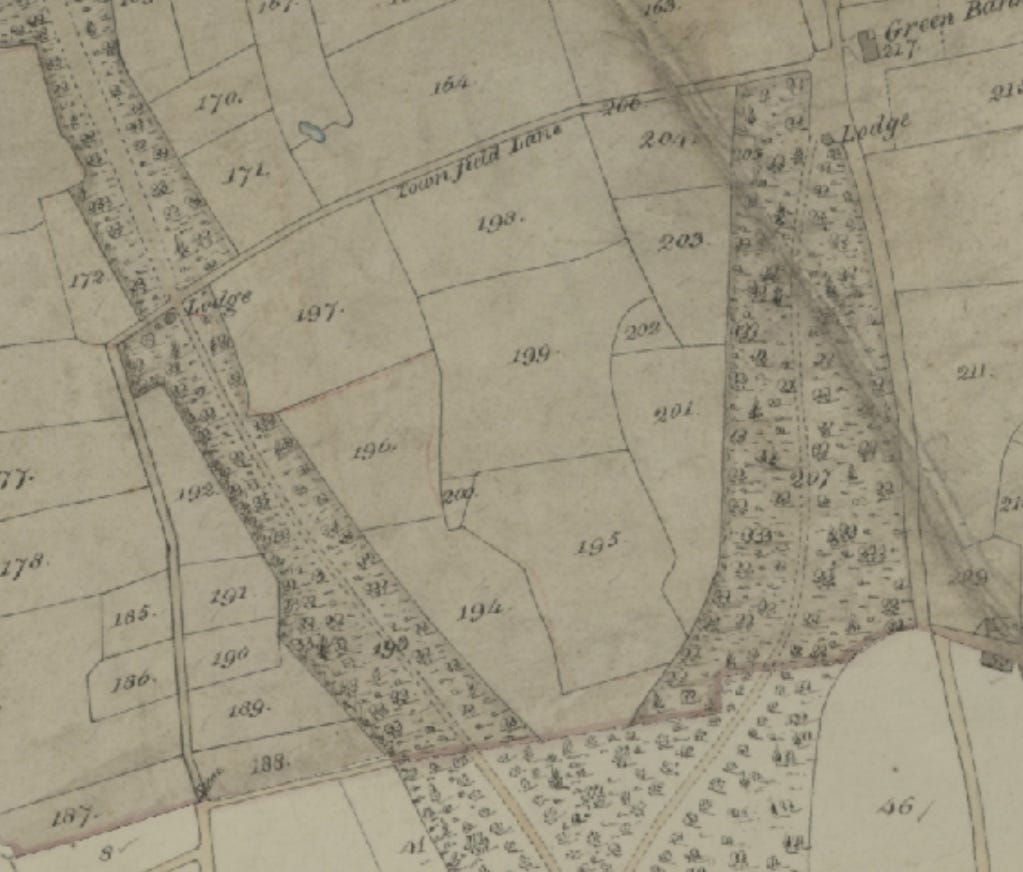

We were later informed by our next door neighbour that this field was also locally known as ‘The Pageant Field’ and was used for community celebrations and gatherings. The 1836-51 tithe maps does not record this name, instead referring to it as ‘Low Hill’ (plot 199). Other adjoining plots share similar names, being “Low Hill Field’ (plot 195) and another ‘Low Hill’ (plot 194), all of which were originally hay fields. Aside from the panorama of mature woodland that surrounds it, the most distinguishing features of the Good Field are the mellow undulations of medieval furrows and two substantial copses of standard and copper beech trees. Scouring a succession of tithe maps, these copses have been there since at least 1875; however, the most interesting feature may be even older.

Roughly in the centre of the field is a small rise, surmounted by six Douglas Firs. This hump is composed of small sandstone boulders and is surrounded to the east by a shallow trench that defines its outline. I recall being intrigued by this feature when I first noticed it, but discounted rough similarities in footprint to sites such as Bryn Celli Ddu, and supposed the location was more likely a collective deposit for any loose sandstone boulders and pebbles that were dredged up by the plough and furrow field system.

Despite this, I still had niggling thoughts. I’d not long finished reading Alfred Watkins’ The Long Straight Track (1925) and the idea of ancient roadways connected by manmade geographical features continued to rattle in my mind. In spite of this, I didn’t pursue the idea due to the lack of comparable ancient burial sites in the local area. This small, stony rise became did however become the preferred site for campfire beers under the wheeling western sky, and any further thoughts of its origins were put by the wayside.

Until now.

Following an interesting conversation with another neighbour, the following information was gifted to me, granting a re-entry into possibly fruitful exploration. The proceeding quote was produced by the Historic Environment Records and concerns the earthwork rise,.

“The Low Field – the HER No. 11211/2 – possible Barrow –

Description: Oral communication to the HER W.Bawn 05/09/2019. A mound like earthwork located in ‘The Low Field’ as named on the tithe map and apportionment c1840. The ridge and furrow earthworks in this field carefully skirt around this feature. Because of its name the ‘low field’ and the shape of the feature, it may be a prehistoric burial mound.

The earthwork is located in a plot called ‘low hill’.

Unless and until archaeologists dig into it, it has to be described as ‘possible’. I’ve also had Peter Carrington look at it and he agrees with Rob Edwards of HER.

Obviously this needs to be interrogated further. Tantalisingly, present day lidar imagery looking from west directly east show the rise (centre left) with the plough furrows clearly parting to accommodate this feature. Though I’m still not ready to fully jump onto the burial mound theory, it is fascinating to imagine we have a potentially ancient mortuary monument on our doorstep.

Even if this isn’t the case, the local area possesses an embarrassment of riches concerning old burial sites; Handbridge is literally built on a large Roman funerary landscape and boasts extensive Victorian and Edwardian cemeteries which flank Overleigh Road. Yet the idea of something far older is still exciting, mainly as it chimes with one of my favourite Jake Stratton-Kent quotes;

“The magician looks about them and sees the magical potential in all things. Has this river no nymph, this mound no hero, this mountain no god? Perhaps under no name known today, but the magician is – like a second Adam – replete with the Power of Naming. Many locations have magical uses or associations, awaiting our use of mythic language. If say, a prehistoric burial mound is associated with no name known now, then ask your spirits which one of them or their companions and allies dwells there. What matter if no-one called the resident by this name before? Names change, but the ancient magic continues regardless. This extends to new places as much as old or rural ones; to any place with meaning for you. Reclaim the landscape, reinvest it with power and significance; be aware of the innate power and significance inherent in every place.”(JSK Geosophia Volume 1 p47)

This re-engagement with spirits of the landscape is eternally inspiring and I’m kicking myself that I didn’t pursue this route in the first place when my suspicions were first aroused. This is a potent reminder to take seriously the idea that landscape can be engaged with in this manner and that it does not necessarily always require the heavy sedimentation of historic records to make it some kind of true. The issue I have is that whilst I’ve talked the talk of animism and engagement, the words have often come quicker than the embodied practice. It’s obviously an ongoing work to fully appreciate and apprehend an animate universe and I realise that these shifts in perception will not happen concurrently. It’s just a disappointment to have had those suspicions whilst being magically operant, and to not have acted upon them.

So what next? Firstly, to act on Jake’s words. The Good Field certainly has a spirit ecology that is palpable, and engaging with the overall genus loci is the obvious primary step. Whether this is done through the local dead, the spirits of the land itself or a combination of both will be a matter of experimentation. Magically, any further work will be entirely based on this first contact so it’s hard to say what shape that further work will take. Also, pursuing less occulted avenues, we’ve the excellent Poulton Research Project close by which may be able to provide evidence and context for other prehistoric burials in the area. Here’s to the ongoing friendship with the spirits of this inspiring and most excellent field.

The occult me would get out in the field and have a play......

The map geek in me would want to look at the map zoomed out to see how the field fits in to the landscape and the surrounding area. Also the map geek in me loves that there are both old and new fields on the small part of the map shown.

Can't wait to read more.